By Dr Lorna Smith, Senior Lecturer in Education (PGCE English), School of Education

By Dr Lorna Smith, Senior Lecturer in Education (PGCE English), School of Education

It is a truism that English is a humane subject and hence that all humanity should be represented and celebrated. Yet there are, in practice, significant hurdles that mean that Black, Asian and minority ethnic students are marginalised in English classrooms. These students rarely see themselves represented in literature; if they are, racial stereotypes are perpetuated; and lessons on these texts are mostly taught by white teachers. This blog focuses on positive action happening in the PGCE English programme to ensure that all students can feel engaged and visible in all English lessons – and that includes learning from some global majority students themselves.

The challenge of representation – in texts and in the teaching population

English educators have long been aware of the problem of (the lack of) representation in the subject English curriculum, and plenty have worked hard over the decades to celebrate Black, Asian and minority ethnic people. For instance, the seminal report A Language for Life makes clear that ‘No child should be expected to cast off the language and culture of the home as he [or she] crosses the school threshold …’ (Bullock, 1975: 4), while the erstwhile Inner London Education Authority published resources on anti-racist teaching in English in the early 1980s (now freely available again via the English & Media Centre).

Yet despite British schools now educating more students of the global majority than ever before, the English offer in many schools is currently rather male, pale and stale. This is partly because the national curriculum for English (DfE, 2014) now requires the study of British authors only at Key Stage 4, which was until recently apparently interpreted by GCSE examination boards as licence to ignore Black and most ethnic minority writers (the largest board, the AQA, has only just added a novel by a Black author, Kit de Waal, to their specification); it is exacerbated by Ofsted’s recent Research Review: English, which implies that some texts featuring what it obliquely describes as ‘contemporary issues’ may lack ‘literary merit’. Furthermore, our research (Smith, 2020; Chapman et al, 2022) has found that even at Key Stage 3, where teachers (in theory) have more curriculum choice, reading lists are dominated by white men writing about white men. And if Black characters do feature, they are the creation of a white author and presented in a demeaning position (Crooks in Of Mice and Men probably being the most famous example). It is therefore not surprising that, lacking mirrors of themselves in books (Bishop, 1990), Black students feel marginalised.

The situation is made more challenging when we consider who is teaching these texts. As highlighted in a recent School of Education blog, almost half of England’s schools have no ethnic minority teaching staff at all. In 2017 in Bristol there were just 26 Black teachers out of 1,346 (0.02%), despite the fact that over 20% of Bristol’s population identifies as other than White British. Recent small-scale research conducted by one of my student teachers suggests that white teachers in one Bristol school are uncomfortable when talking about issues concerning race and ethnicity with Black students, despite being happy talking about the same issues with white students. It is perhaps no coincidence that the Centre of Dynamics of Ethnicity in collaboration with the Runnymede Trust found that in 2017 Bristol had the 3rd highest level of educational inequality in England and Wales in terms of qualifications and progression to further and higher education.

Tackling Diversity in Teaching

For a group of Black Year 8 girls at Montpelier High School, enough was enough. They were frustrated both because they could not see themselves in the curriculum, and because some of their teachers lacked cultural awareness, which sometimes resulted in them unwittingly mis-pronouncing individuals’ names in lessons and making unhelpful assumptions due to unconscious bias. So, in May 2022, the girls spoke to their form tutor, Jess Bray, an alumna of the PGCE English course, who helped them organise themselves and create positive change. Tackling Diversity in Teaching – also known as TDT, or The Dream Team – was born. Together, TDT put together a presentation for the whole staff at their school, which was so well received that they were subsequently invited to speak to staff in other Bristol schools too, and the group grew.

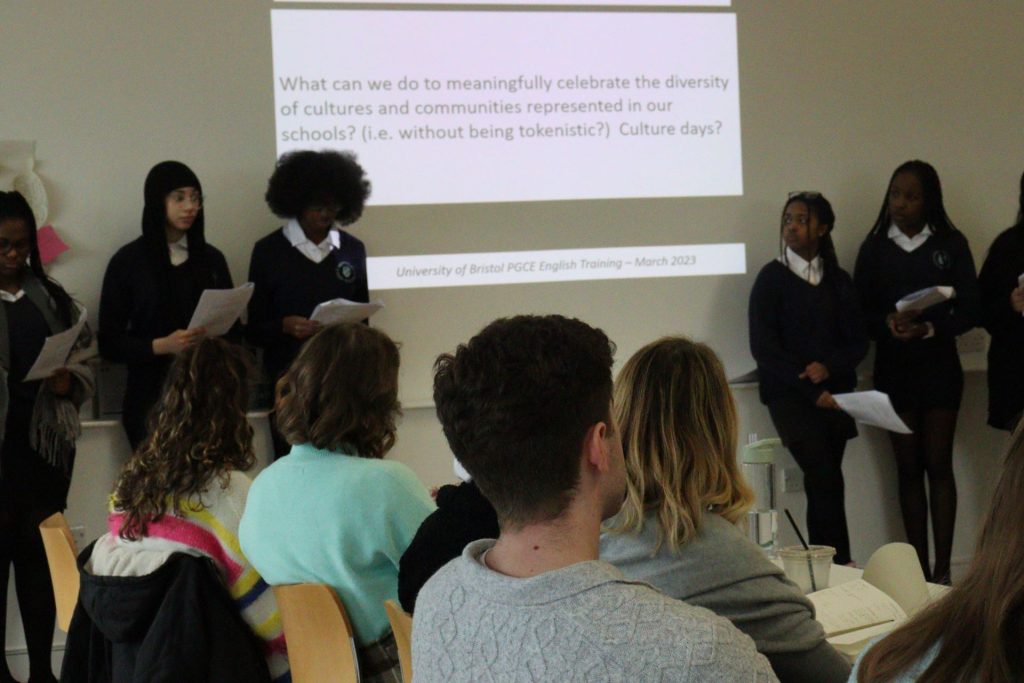

Jess then got in touch with me, offering to bring TDT into the School of Education to work with the current English PGCE cohort. Given that the PGCE English tutors had already planned that diversity and decolonisation would be the theme of a PGCE Recall Day – building on our own research (see Further Reading below), the inspiring Lit in Colour project and the wonderful Cargo Classroom) – including TDT fitted perfectly. So, in early March 2023, we were delighted to host TDT students Cymora, Adama, Sasha, Danitor, Alexia and Ayesha to the School of Education, alongside the PGCE English student teachers who were back in University for a day during their long teaching placement.

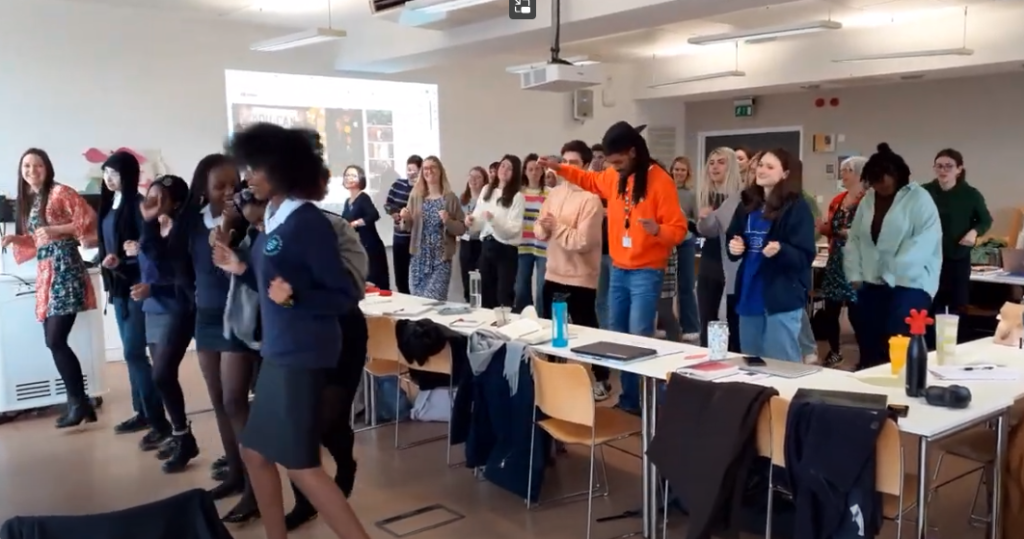

In advance of the day, the TDT team had put together a short presentation about themselves, and the student teachers came up with a range of questions for TDT. TDT then worked out responses to the questions and prepared the presentation for the event. There was an unexpected joyful moment on the day for the student teachers, when TDT announced that they would be teaching us the Candy Dance at the end of the session.

As we wrote in this news article, TDT made a fantastic contribution to our Recall Day, and the student teachers were effusive in their thanks. TDT spoke from a real position of expertise and experience, sharing their suggestions, strategies, and advice with honesty and grace. They gave us all plenty to enrich our teaching practice and develop awareness of and confidence in teaching diverse texts, and we all loved learning the Candy Dance.

Take aways

We hope that the impact will cut two ways – that the PGCE English cohort will now feel even more prepared and confident to work in racially and ethnically mixed classrooms, and to teach diverse texts well; and that the Tackling Diversity in Teaching group and their peers will go on to enjoy and flourish in their English lessons. The need is urgent and important. If students do not see themselves reflected in the texts they read in English in Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4, they are less likely to go on study English at A level. They are thus less likely to go on and study English at university. And unlikely, too, to even consider English teaching as a profession. There is a need to create a new virtuous cycle. We hope that, with TDT’s help, we have begun to do so.

References

Bishop, R. S. (1990) Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6 (3).” Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom 6.3 ix-xi.

Bullock, A. (1975) A Language for Life: Report of the Committee of Enquiry appointed by the Secretary of State for Education and Science under the Chairmanship of Sir Alan Bullock F.B.A. London: HMSO

Chapman, S., Kneen, J et al (2022) Teaching Key Stage 3 literature: The challenges of accountability, gender and diversity Literacy, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12288

Smith, L (2020) Top Ten Texts: A Survey of Commonly-Taught KS3 Class Readers. Teaching English. 23, 30-33. 4p

Further reading

Smith, L., Thomas, H. et al (2022) The dance and the tune: a storied exploration of the teaching of stories. Changing English, 29 (1). pp. 40-52. ISSN 1469-3585

Watson, A. et al (2022) Teacher agency in the selection of literary texts. English in Education. 56 (4) pp. 340-356

School of Education PGCE Programmes

To find out more about the School of Education PGCE programmes, visit our website: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/education/study/initial-teacher-education/

Black Bristol PGCE Scholarship programme

The University of Bristol are committed to addressing the lack of representation of the Black heritage community in teaching and higher education across the UK.

It will annually fund up to 4 Black and mixed-Black heritage students at the University of Bristol, enrolled on the School of Education’s PGCE (Postgraduate Certificate in Education) Initial Teacher Education programme.

Find out more, including details and eligibility, about the scholarship programme for additional funding for Black and Mixed-Black Heritage UK applicants, which goes toward the cost of undertaking a PGCE course starting in 2023-24.

https://www.bristol.ac.uk/education/why-soe-bristol/black-bristol-pgce-scholarship/