Blog post by Rhiannon Moore (PhD student, School of Education, University of Bristol) and Anustup Nayak, (Project Director for Classroom Instruction and Practice, Central Square Foundation)

Blog post by Rhiannon Moore (PhD student, School of Education, University of Bristol) and Anustup Nayak, (Project Director for Classroom Instruction and Practice, Central Square Foundation)

What do we know? Teacher motivation and student learning

Teacher motivation is a commonly discussed topic within policy and research in LMICs. Such discussions tend to have two main points of focus: firstly, that teacher motivation is worryingly low; and secondly, that this is having an impact on student learning. In this blog, we are particularly interested in exploring the latter of these two points. We largely focus our discussion on teachers in India, where our experience and research suggests that it may be helpful to consider this relationship as a two-way cycle instead of an input-output process. Thinking about teacher motivation in this way can change the way we think about both teachers and students, asking that we challenge the often over-simplified picture of a poorly motivated teacher whose behaviour inhibits their students’ learning, and instead start to consider teachers as dynamic agents whose own needs may not be being met.

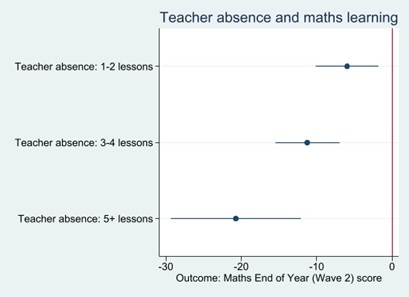

We start this blog with the acknowledgement that, within existing international literature and research, there is a lot of evidence that higher teacher motivation is associated (either directly or indirectly) with greater student learning. Teachers who are more motivated are found to engage more with professional learning opportunities and therefore to use a wider range of teaching practices. They are also more able to motivate their students to enjoy their time in the classroom. In contrast, lower levels of teacher motivation are associated with teacher behaviours and classroom practices which make it harder for students to learn, including teacher absence from lessons. Findings from our own ongoing work align with this: analysis of Young Lives data from Andhra Pradesh and Telangana indicates that teacher absence from lessons is strongly associated with lower levels of maths and English learning among secondary school students[1], even when we control for other differences between students, teachers and schools.

Figure 1: The relationship between teacher absence from lessons in the past two weeks and student learning in Grade 9 (compared to a teacher with no absence)

Figure 1: The relationship between teacher absence from lessons in the past two weeks and student learning in Grade 9 (compared to a teacher with no absence)

Note: This graph shows the regression coefficients from a four-level multilevel model which also includes controls for a range of school, teacher and student context variables. For simplicity of presentation, only those variables related to absence are presented in this graph.

Such evidence forms the basis of the many educational interventions aimed at improving student learning through changing aspects of teacher behaviours. Frequently this means targeting things thought to be associated with lower professional motivation, including the use of incentives to improve teacher classroom attendance and the use of performance related pay to increase teacher effort.

The other side of the cycle – how does student learning shape teacher motivation?

But while the focus of ‘teacher motivation’ research is (understandably) centred on teachers, this seems to risk ignoring the fact that they are not working independently but instead are embedded within a system which often places huge demands on teachers while giving them little professional autonomy. Many are working within challenging conditions on a day-to-day basis: within the Indian context (as in other LMICs), learning levels are low, with children entering the classroom with learning far below their expected grade level; while schools (particularly in rural areas) are often small and isolated, offering teachers few opportunities for peer support or professional growth.

Being a teacher in this context is far from an easy job, and this is particularly the case if training has not fully prepared you for the role. We know that teaching is cognitively demanding, with teachers making over 1500 decisions a day inside the classroom (much the same as a doctor or engineer). Yet, around the world, many teachers walk into the classroom without the training, monitoring or support they need to make these decisions to the best of their ability. Minus the right tools and training, teachers’ “success rate” with students reduces, understandably leading to feelings of incompetence and low self-efficacy in their ability to support students. Likewise, existing research from other contexts suggests that the likelihood of teacher burnout is greatest where teachers do not feel efficacious in their role – including in situations where they “perceive […] they have low levels of control over discipline in their classrooms […], where there are low levels of student interest and involvement […], and where there is low student respect for teachers.”

Taken together, the existing evidence base highlights how the different kinds of interactions teachers have with students can inform their professional motivation, revealing that while “[the] quality of the relationship between teacher and pupils can be one of the most rewarding aspects of the teaching profession […] it can also be the source of emotionally draining and discouraging experiences”. Evidence from Turkey supports this, indicating that teachers gain motivation from their students’ successes – and that this happens even when teaching is otherwise challenging or unrewarding. We also know that parental appreciation of teachers is a critical element of motivation – and that the reverse is also true: where children don’t succeed to the levels their parents expect, teachers can often face blame from parents, the community, and from society more widely, with implications for wider workforce motivation and for subsequent efforts to recruit new candidates to the profession.

What does this mean for how we think about teacher motivation?

These findings have implications for how we talk about teacher motivation – as well as how interventions might seek to improve it. Far from being just an ‘input’ into student learning which can be addressed through policies such as teacher incentives, instead it seems it may be better defined as an ‘outcome’ in itself, shaped by the working context, education systems and broader processes within which teachers work.

In short, to address low levels of teacher motivation, it seems that we need to ensure that teachers are given the tools they need to succeed – and relevant and timely support structures which help them while they learn to use them. The evidence we look at above appears to suggest that motivation is shaped by teachers’ professional skills, their feelings of efficacy and the chance of seeing success in their classrooms. This requires a new way of approaching professional motivation: one which is ‘teacher-centric’ without being ‘teacher-blaming’. It also suggests something else – which is that, in itself, teacher motivation might not be the educational ‘silver bullet’ it is sometimes portrayed to be. Instead, perhaps it is more helpfully understood as an indicator of how the system still needs to improve – a litmus test of whether education is meeting the needs of both teachers and their students.

[1] We recognise that absence can be related to many different factors, and is not only a result of lower levels of teacher motivation.