By Debbie Williams, School of Education, University of Bristol

By Debbie Williams, School of Education, University of Bristol

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) is an international human rights treaty that encompasses fifty-four articles that advocate the rights of each child (CRC, 1989). The most influential (and contentious) of these children’s rights — in accord to much literature (Freeman, 2009; Lundy et al., 2019; Archard, 2020) — is Article 12 (respect for the views of the child):

‘1. States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child.’ (CRC, 1989, p.5)

This Article somewhat advocates regard for each child’s views and their right to be heard (Archard, 2004). There is no stipulation as to how these views ought to be expressed. Though ‘views’ are implicitly synonymous to ‘voice’ and ‘voice’ is contentious (Alexander, 2010). I implore that we consider ‘children’s voice’ not as a singular but rather a plurality of ‘children’s voices’ to advocate a more inclusive and informed implementation of this instrumental children’s right.

What is Children’s Voice?

Children’s voice recognises children’s valuable contributions (attitudes, beliefs, feelings, thoughts, and preferences) to matters in their own lives, and for these to be heard (Murray, 2019). Children’s voice infers ‘children’ as an homogenous group— a ‘singular children’s voice’ (Lomax, 2012, p.18)— whom can verbally communicate their voice through conventional, verbal utterances (Bradwell, 2019). The pervasiveness of this conventional ‘voice’ remains a hindrance for children whose voices do not conform to society’s conventions (e.g., young children, children with labels of special educational needs/disabilities (SEN/D), and children from minority communities) (Lansdown, 2011; Kallio, 2012). To acknowledge ‘voice’ as a singularity does not account its diverseness rather propagates a hegemonic hierarchy between children who ‘can’ or ‘cannot’ verbally communicate.

What are Children’s Voices?

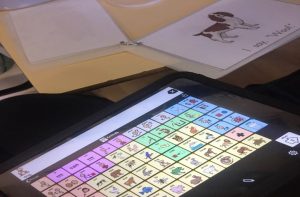

Children’s voices encapsulates the diverse communicative potential that all children possess in which to express their views. That verbal (speech, vocal sounds) and nonverbal (facial expressions, gestures, silences) communication ought to be held in equal regard (Spyrou, 2011). Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) (assistive technologies, Makaton, picture exchange communication system (PECS), photovoice, etc.) can empower all children to express their voices (Cranmer, 2020). These communication technologies may not reflect a child’s authentic voice as these tend to solely accommodate basic communication (Andersen, 2010). To capitalise on Article 13 (freedom of expression) children’s voices need not be confined to verbal communication as other forms of expression ‘orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice’ are cited (CRC, 1989, p.5).

Does Plurality Really Matter for Children’s Rights?

Children are not an homogenous group (Montgomery, 2013). Children are a marginalised group (Bradwell, 2019). Their marginalisation is further exacerbated through their status in other group(s) (e.g. age, disability, ethnicity, indigeneity, language, etc. (United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2019). These multifarious voices are not being heard:

‘all children and young people—whatever their communication and/or cognitive impairment—have something to communicate’ (Morris, 2003, p.346)

Therefore, we must seek to authentically understand all children’s experiences and views (ibid.). That it is not the child’s onus to prove their capacity to communicate, it is our onus to disrupt the conventional ‘voice’ and advocate the multiplicity of all forms of communication and voices (Bradwell, 2019). To this end the plurality of ‘children’s voices’ does matter not least for the realisation of all other CRC rights (Alderson, 2008) but also to empower those children who would otherwise go unheard (Alexander, 2010; Lansdown, 2011).

References

Alderson, P. (2008) Young people’s rights: Children’s rights or adult’s rights? Youth and Policy. 100, pp. 15- 26.

Alexander, R. (2010) Children’s voices. In: Alexander, R. (2010) Children, their World, their Education: Final Report and Recommendations of the Cambridge Primary Review. London: Routledge, pp. 143- 157.

Andersen, L. E. (2010) Picture exchange communication system for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals. 73, pp. 80 -87.

Archard, D. (2020) Hearing the child’s voice: A philosophical account. Journal of the British Academy. 8 (4), pp. 7- 15.

Archard, D. (2004) The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In: Archard, D. (2004) Children: Rights and childhood. London: Routledge, pp. 58- 70.

Bradwell, M. (2019) Voice, views and the UNCRC Articles 12 and 13. Journal of Early Childhood Research. 17 (4), pp. 423- 433.

Cranmer, S. (2020) Disabled children’s evolving digital use practices to support formal learning. A missed opportunity for inclusion. British Journal of Educational Technology. 51 (2), pp. 315- 330.

Freeman, M. (2009) Children’s rights as human rights: Reading the UNCRC. In: Qvortrup, J., Corsaro, W. A. and Honig, M-S. (2009) The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 377- 394.

Image 1: Learn About: AAC & More – Educational Assistive Technology (weebly.com)

Image 2: www.vorpalina.com/guia-breve-de-comunicacion-efectiva/

Kallio, K. P. (2012) Desubjugating childhoods by listening to the child’s voice and childhoods at play. An International Journal for Critical Geographies. 11 (1), pp. 81- 109.

Lansdown, G. (2011) Every child’s right to be heard. London: Save the Children UK.

Lundy, L., Tobin, J. and Parkes, A. (2019) Article 12 The right to respect the views of the child. In: Tobin, J. (2019) The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: A commentary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 397- 435.

Montgomery, H. (2013) Introduction. In: Montgomery, H. (2013) Local Childhoods, Global Issues. Bristol: The Policy Press, pp. viii- 1.

Morris, J. (2003) Including all children: Finding out about the experiences of children with communication and/or cognitive impairments. Children & Society. 17, pp. 337- 348.

Murray, J. (2019) Hearing young children’s voices. International Journal of Early Years Education. 27 (1), pp. 1- 5.

Spyrou, S. (2011) The limits of children’s voices: From authenticity to critical, reflexive representation. Childhood. 18 (2), pp. 151- 165.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2019) For Every Child, Every Right: The Convention on the Rights of the Child at a Crossroads. New York: UNICEF.

United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (1989) The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available from: https://www.unicef.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2016/08/unicef-convention-rights-child- uncrc.pdf [Accessed 18 September 2022].

About the Author

Debbie Williams is an EdD student (School of Education, University of Bristol).

Debbie Williams is an EdD student (School of Education, University of Bristol).

Her Doctoral research advocates children’s rights and calls to disrupt the conventional ‘voice’ in education.