Reflections after an EdJAM dialogue between UK and Pakistan university students. Blog by Kerry Parsons, BSc Education Studies, School of Education.

Reflections after an EdJAM dialogue between UK and Pakistan university students. Blog by Kerry Parsons, BSc Education Studies, School of Education.

Why is my knowledge limited about the colonial past, the violence and the colonial structural legacies that still exist today?

I am a mature student in Education Studies at the School of Education, University of Bristol. One of my second-year units, ‘Education Viewed from the Global South’, has broadened my understanding of the continued colonial structures through past and present education. Knowledge hierarchies and dominant narratives have been a prominent discussion in this unit. Each weekly topic focused on a different southern scholar from across the global south and we were encouraged to critically discuss the varied educational theories and lived experiences of colonialism.

Alongside this unit, my Education in Practice placement was with the Education Justice and Memory (EdJAM) network who are committed to creative ways to teach and learn about the violent past, to build more just futures. Whilst working with the EdJAM, History Education team in the UK, I have had the pleasure of meeting the wider EdJAM network of researchers, educators and civil society organisations working in the arts, education and heritage from Pakistan, Cambodia, Colombia and Uganda. I have been lucky enough to attend several online workshops and hear different narratives and voices teaching and understanding the violent colonial past.

Of course, I did have a limited understanding of colonialism before I began my studies in the School of Education. However, my understanding of colonialism did not come from my formal education. My limited understanding was gained from reading, social media and documentaries. But how much did I really understand? How many other students felt this way?

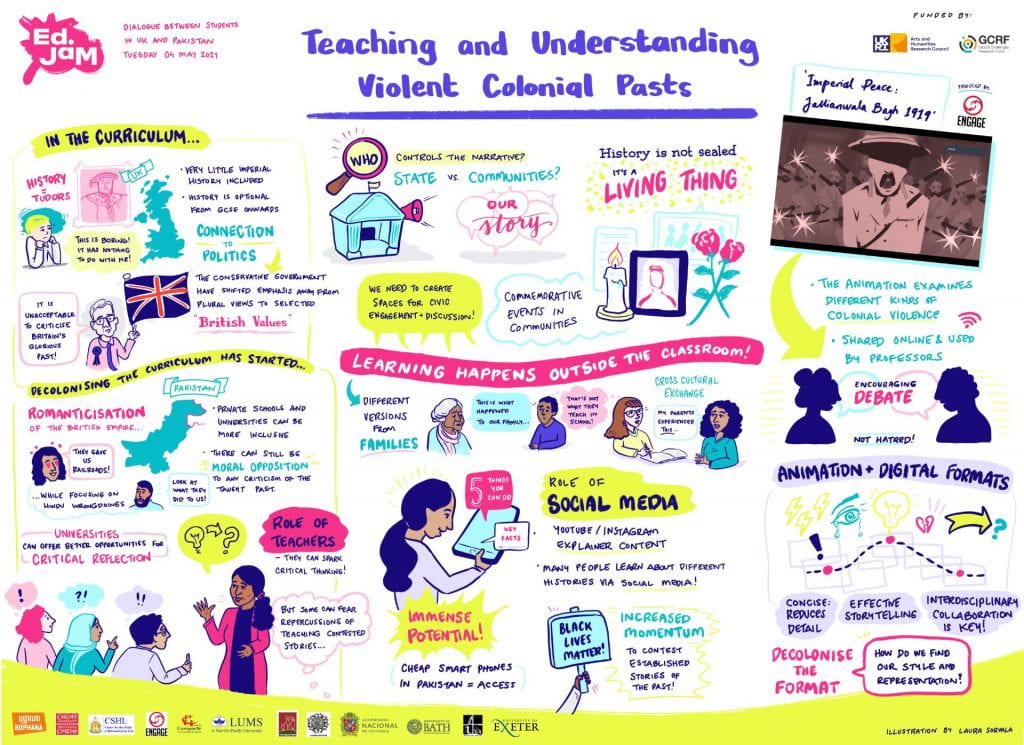

Student Dialogue: Teaching & Understanding Violent Colonial Pasts

EdJAM network arranged an online workshop on the 4th May 2021 hosted by Dr. Sameen Ali, Dr. Tania Saeed and Prof. Catriona Pennell. The workshop brought together final year undergraduate and post-graduate students of History, Education, and Political Science from the UK and Pakistan to encourage transnational and cross-cultural reflection on the broad theme of history and colonial violence. This workshop took place online and was not recorded to give students a safe space to be able to have an open discussion about their own experiences. The aim of this workshop was to discuss:

• How can a more nuanced, inclusive understanding of the colonial past be achieved?

• Where are the silences in popular understanding of British and Pakistani imperial history?

• Why is there an increasing tendency to frame discussions of imperial history around a moral balance sheet – evaluating the past as either ‘good’ or ‘bad’, instilling ‘pride’ or bringing ‘shame’? What are the consequences of this binary approach?

• How does the relative quiet in respective education systems about controversial aspects of colonial history compare with the way politicians in the UK and Pakistan discuss these issues?

• What were the experiences of students from Pakistan and the UK regarding imperial colonialism and coloniality?

Engage Pakistan have created an online space (Hashiya Online) to engage with difficult conversations about colonial histories. Hashiya online produce animated historical documentary short films to educate and inform people about the violence of the colonial past. To open the workshop discussion, a short-animated film, Jallianwala Bagh 1919, was shown to the participants.

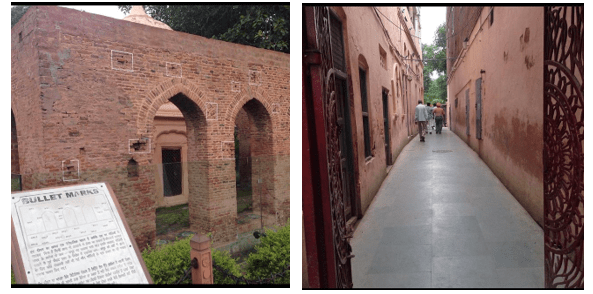

Imperial ‘Peace’: Jallianwala Bagh 1919 . “On 13th April 1919 a crowd of unarmed Sikh, Muslim, and Hindu men and women protesting colonial policies, the British Indian Army fired round after round of live ammunition, goaded on by Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer.” (Hashiya Online 2021).

The images below are of Jallianwala Bagh in the present day (with thanks to Sameen Ali for sharing these images taken by her in 2016). The image below left shows the bullet marks in the wall at Jallianwala Bagh and on the right is of the narrow alley which was the only exit from the Bagh in 1919.

Fatima, one of the researchers and production team of Hashiya Online explained that their animations have been available to view online during the pandemic and has created a space to encourage debate. The long-term aim is to take these colonial stories into classrooms in Pakistan and open critical discussions. Responses to the Hashiya Online animations have largely been positive and opened critical debate and discussion in the online comments sections. Fatima explained that they had anticipated some negative feedback in the online comments because some people are against critique of the state.

However, these comments have opened debate rather than created tension, people who have viewed the animations online have interacted well and some people are able to make parallels with current issues. One example of feedback was a Professor who contacted the Engage Pakistan team. The Professor had been using the animations in their classroom to introduce students to the basic concepts of colonialism. Fatima recalled that her own education did not include discussions around colonial violence and her own introduction to the topic came through social media.

How have colonial pasts been represented in the educational experiences of other attendees?

Participants from the UK and Pakistan felt that their education did not address the violence of colonial history in any depth, if at all. Attendees had different educational backgrounds: students who had international schooling which delivered a British curriculum, and some who had studied in either the UK or Pakistan (or had experienced education in both the UK and Pakistan).

Contributors commented that their own experiences of history during secondary education had been limited by the curriculum. The British secondary historical curriculum covered the Tudors, Victorians and Medieval kings and queens. One participant commented that the limited curriculum put them off studying History as a subject further as they found it boring and ‘did not see themselves’ in the content.

It was felt there were no opportunities or space to discuss colonial history during their limited history education and that there was only space to discuss the colonial past once at University. However, for Universities in the UK and Pakistan, teaching about the colonial past was dependant on the teachers, the University, the subject of study and even decade of study.

There was a recollection by a UK undergraduate in the 90s that there had been discussions around colonialism by lecturers, however, it was not discussed in-depth, and did not address violence or injustice. He recalls that lecturers had said ‘The violence of colonial history was put in a box not to be opened’.

Education about the colonial past seems to have no constant platform in either country, which leads to different ways of knowing and understanding the truth. This is unlike the constant of a limited historical curriculum that participants of this workshop from both the UK and Pakistan have experienced in their secondary education.

Who controls the narrative?

It is not just formal education that influences our historical knowledge, there are also state and political narratives, media narratives and community influences. The UK state curriculum includes ‘British Values’. The realities of the violent colonial past are not part of this state narrative of ‘Britishness’.

Some participants from Pakistan and the UK commented that when they had been educated about events of violence of the colonial past, it came from lived experiences of family members. These lived experiences and family narratives conflicted with the colonial history of the textbooks, formal education, and the state narratives. Community and family histories also differ from the experiences of other families and communities. History does not have one narrative, history is an open discussion, history is a living thing which includes many voices and experiences.

Partition was an example given, and how process for remembering it relate to the teaching of Indian and Pakistani independence. The state narratives of the violent colonial past do not include all the voices and experiences. In the UK and Pakistan these dominant state narratives have been at odds with community voices and historical lived experiences excluded from their versions of the past.

How do Engage Pakistan research and gather information?

The discussion of multiple narratives in our history education, contrasting versions and realities of colonialism explain why there is a lack of understanding. Given that there are multiple narratives and truths, raised the question: How do Engage Pakistan gather materials and develop narratives for their short documentary films?

“In the context of Jallianwala, a lot of academic literature was already available and accessible to us. In context of our other creative content — say with videos on the persecution of the Ahmadi community — we have had consulting academics to help develop our scripts. They have also shared with us archival material and photographs that provide us visual material to supplement the videos.” (Hashyia Online 2021 – Rana Saadullah Khan)

The quote from Rana explains their extensive research as part of the process to create these short films. Engage Pakistan have a team that research the academic literature and consult relevant academics to examine the historical materials shown in their short films. Through this dedicated work Engage Pakistan and the Hashyia Online team develop scrips and create a realistic narrative of educational material that is free to access online.

Decolonising the curriculum and the role of teachers in encouraging critical thinking

Teacher education and pedagogy in classrooms is key to creating safe spaces for student discussion of the colonial past. Prof. Catriona Pennell explained that teachers in the UK education system often have a limited knowledge of colonial history themselves. History teachers at secondary schools in the UK are not necessarily history graduates, they may have studied another humanities subject at undergraduate level.

For example, after teacher training, a graduate in Religious Education may have to deliver the history curriculum to secondary school students as an ‘humanities teacher’. “Then there is also a danger that the inclusion of BAME histories becomes tokenistic. For example, Walter Tull (the first Black Officer in the British Army, killed in action in March 1918) is often wheeled out as the token example” Catriona explained.

Following recent protests, such as Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall, there have been opportunities for teachers to have these critical discussions with their students. Some schools, Local Authorities and academy trusts are taking decolonising the curriculum seriously. There are some resources available from community organisations to support teachers in the classroom.

Charting African Resilience Generating Opportunities (CARGO), a Bristol based community organisation have created resources that celebrate African and African descendent histories and individuals. CARGO’s educational resources are available online and can be included in the curriculum to support classroom discussion.

My interpretation of the student dialogue workshop discussions above are only a snapshot of such a vast, interesting and important topic. There are many elements, narratives, voices and stories to include in teaching about the violence of colonial pasts and the structural legacies that remain today. The narratives that have limited our knowledge and our education are only one element of the structural legacies of colonialism.

Participants were asked if there were any insights from the discussion that they intend to take forward with you in your studies and/or career?

“It was very interesting and related to my studies in Political science “

“There are many forms of colonial violence – some continuing even today.”

“Yes…the fact that these issues are hard to find in our syllabi “

Are your educational experiences reflected here?

References

If you would like to keep up to date with EdJAM’s work and hear about future events, please subscribe to the mailing list

This graphic illustration capturing the conversations during the Student Dialogue: Teaching & Understanding Violent Colonial Pasts was created by Laura Sorvala.

Website: https://www.laurasorvala.com

Twitter: @_auralab