A School of Education Reflection by Pier Luc Dupont Picard and Alison Oldfield

In March 2023, a group of students and staff at the School of Education came together to learn about how climate justice and decolonising work are inextricably linked. We discussed the educational implications of decolonising and decarbonising agendas, reflecting on what this means for our theory and practice as students, researchers, and teachers. In this short post, we share some of our thoughts and provocations.

We read three texts which we discussed in-depth during our first meeting together. Kyle Whyte’s Indigenous climate change studies: Indigenizing futures, decolonizing the Anthropocene helped us consider the continuities between the ecological and social crises, including forced displacements, brought about by current environmental changes and those induced by settler colonialism.

An indigenous perspective illuminates how anthropogenic climate change merely intensifies centuries-old environmental changes linked to European imperialism, capitalism and industrialisation, which have radically impacted indigenous cultures, health, economies, and politics. In this sense, indigenous knowledges cannot only suggest more sustainable ways of relating to nature but also reveal what it is like to live in a ‘post-apocalyptic’ world – including what adaptation in that world requires.

Similarly, in Farhana Sultana’s commentary piece, Critical Climate Justice, we learned about the region-specific harms and oppressions linked to climate change and the historical responsibility of industrialised societies which have benefited from the carbonisation/colonisation of the atmosphere.

We also examined the contribution of feminist ethics and methodologies, centred around care, dialogue and collaboration, to the understanding of climate injustices and the development of reparative policies and practices. Crucially, Sultana signals the important role of education to help us ‘unlearn to relearn’, a phrase that highlights the limitations of institutionalised knowledges and the priority that should be given to subaltern perspectives in climate justice debates.

Foluke Adebisi’s blog on ‘Global University Rankings and Toilets’ provoked quite a bit of discussion about the metrics of success in education, and how these can hamper critical thinking on decarbonising and decolonising. When universities’ prestige is tied to their capacity to produce research published in a limited number of leading journals edited in the Global North, which in turn determines funding from wealthy governments and philanthropists, the interests, experiences and skills of the global majority are likely to be overlooked. Partnerships with grassroots organisations can mitigate these biases, but only if these organisations have the opportunity and power to challenge established research paradigms and questions.

In our second meeting together, we focused on what decolonising and decarbonising education might look like, particularly if we take their intersections seriously. This included presenting theories and concepts in their historical and political context, therefore avoiding the depiction of modern European perspectives as universal and intemporal. Global South thinkers should be put front and centre rather than discussed as an alternative way to qualify or complement an established canon.

The use of land and other natural resources could also be addressed as a fundamental matter of justice across a range of subjects. In their daily practice, educators can create safe and stimulating spaces for students to research and debate prevailing ideas, listening to and respecting a variety of lived experiences, as the realities of colonisation and carbon-intensive living plays out differently and in complicated ways across contexts. They can also push for more structural changes in the demographics of students and staff, especially in elite universities which remain disproportionately white.

While the discussion engaged with education more broadly, it also drilled down into what this means for us as members of a community here in the School of Education. Many of the practical ideas shared here aligned with principles and pedagogies we would aspire to across learning, teaching and research. But these also highlighted tensions between what decolonising and decarbonising education might mean alongside constraints of institutional, national and international educational trends and systems.

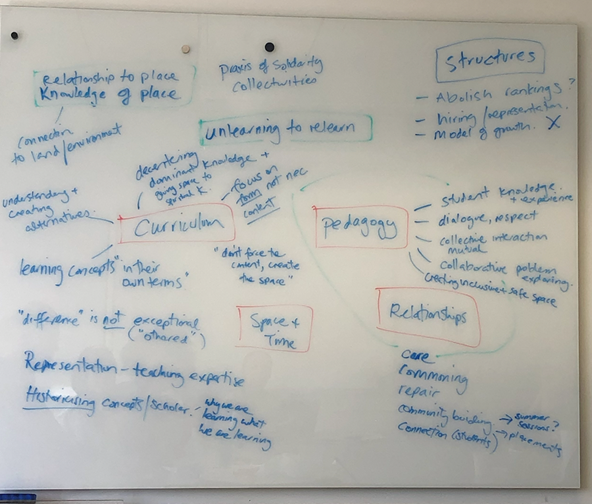

However, we collectively developed a set of ideas that combined principles to work towards and everyday commitments to work on – see the photo for the colourful outcome of this discussion. Highlights included making visible the value and contribution of indigenous knowledge in historical and geographical contexts, while also remembering they may be different to our own; talking about the value of our research beyond the use of evaluations and metrics that elevate certain knowledge traditions at the expense of others; reframing curricular structures and timelines to de-centre Western theories of learning and knowledge as the first port of call; prioritising relationships among students and educators, framed by mutual learning and care and holding space in the building and interactions with each other so that we might unlearn and relearn together.

We hope the discussions we had during the reading group will continue and be supported through action across the School of Education in the months ahead.